Understanding Art Therapy

Art therapy is a psychotherapeutic approach that harnesses the creative process to enhance mental, emotional, and physical well-being. Unlike traditional talk therapy, which relies on verbal articulation, art therapy invites children to express themselves through drawing, painting, sculpting, or collage-making in a safe, non-judgmental environment. This is particularly powerful for children, who often lack the linguistic maturity to express complex emotions like fear, grief, or joy. As Malchiodi (2012) notes, children under 10 frequently struggle to verbalize abstract feelings, but art provides a direct pathway to their inner world, engaging the right hemisphere of the brain associated with emotional processing (Hass-Cohen & Carr, 2008).

Far from being limited to pathology or disability, art therapy is a universal tool for nurturing emotional intelligence, resilience, and creativity. It allows caregivers and therapists to monitor a child’s psyche, offering insights into their emotional states without invasive questioning. Through art, children develop skills in emotional regulation, problem-solving, and imagination while fostering self-esteem and strengthening bonds with caregivers. This holistic approach makes art therapy a joyful, instinctive practice that resonates with children’s natural inclination toward creative play.

Key Principles of Art Therapy for Children

Art therapy’s efficacy for children rests on five core principles, each supported by psychological and neuroscientific research:

-

Non-Verbal Expression

Children often lack the words to express complex emotions, but art provides a safe, non-verbal medium for communication. Research shows that art-making activates the brain’s right hemisphere, facilitating emotional expression where verbal skills fall short (Hass-Cohen & Carr, 2008). This is particularly valuable for young children or those with developmental delays, as it bypasses linguistic barriers. -

Safe and Playful Medium

Art therapy leverages children’s natural love for play, creating a non-threatening environment where they feel safe to explore. Neuroscience research indicates that creative activities reduce cortisol levels (the stress hormone) while increasing dopamine, fostering feelings of pleasure and safety (Shonkoff & Phillips, 2000). A 2015 study found that art therapy settings lowered anxiety in pediatric populations, enabling freer expression (Drake et al., 2015). -

Emotional Regulation

Tactile and repetitive art activities, such as moulding clay or colouring, stimulate the parasympathetic nervous system, promoting calm and reducing emotional distress (Van der Kolk, 2014). A study in The Arts in Psychotherapy showed that children engaging in art therapy exhibited significant reductions in anxiety, as measured by standardized scales (Slayton et al., 2010). For example, a child might channel frustration into vigorous brushstrokes, learning to self-soothe through the creative process. -

Self-Discovery and Identity

Art therapy supports children in constructing a coherent sense of self, a critical developmental task (Erikson, 1968). By creating self-portraits or symbolic collages, children explore their identities and build confidence. A 2018 study found that art therapy improved self-concept and resilience in children, as reported by both children and caregivers (Cohen-Yatziv & Regev, 2018). -

Adaptability to Diverse Needs

Art therapy’s flexibility makes it effective across a range of abilities and experiences. A meta-analysis in Clinical Psychology Review confirmed its positive outcomes for children with disabilities, trauma, or developmental delays, with effect sizes comparable to traditional therapies (Reynolds et al., 2000). Whether a non-verbal autistic child uses finger painting or an older child processes grief through narrative drawings, art therapy adapts to meet them where they are.

These principles highlight why art therapy is uniquely suited to children, offering a gentle yet powerful way to support their emotional and cognitive growth.

Tapping into the Unconscious

One of art therapy’s most remarkable strengths is its ability to access the unconscious mind, where emotions, memories, and instincts reside beneath everyday awareness. As theorized by Freud and Jung, the unconscious holds repressed feelings and experiences that shape behaviour (Jung, 1964). Neuroscience supports this, showing that creative tasks engage the limbic system and right hemisphere, bypassing the structured reasoning of the prefrontal cortex (Schore, 2012).

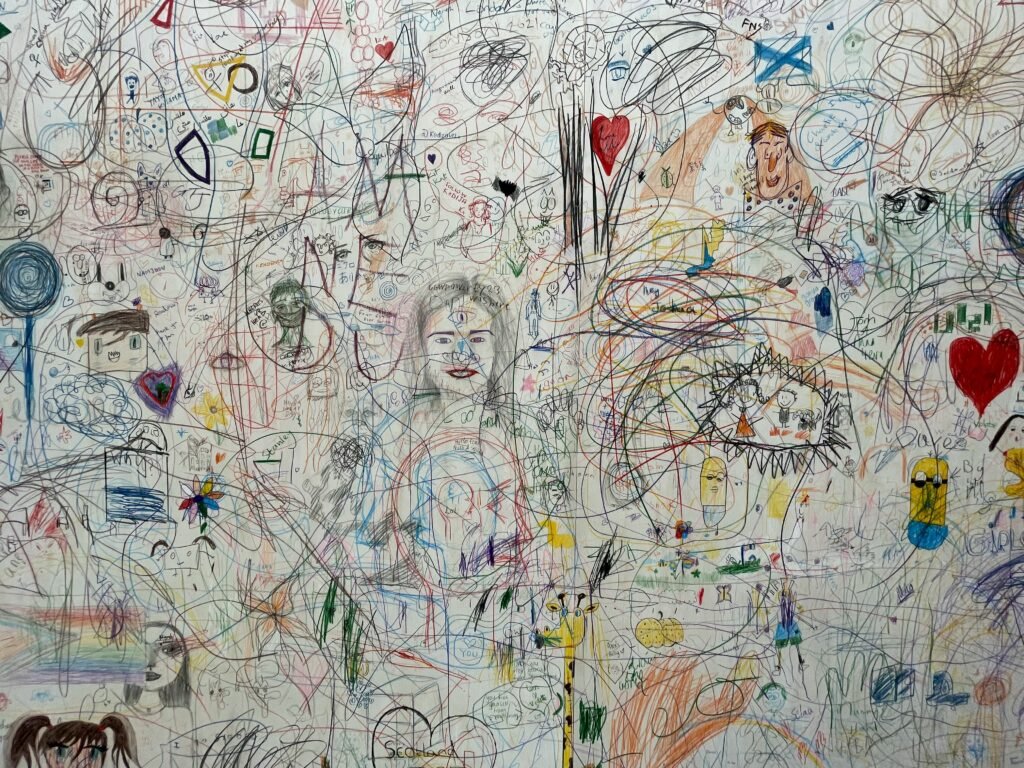

This process is particularly valuable for children, whose verbal capacities are still developing (Piaget, 1970). A 2017 study found that spontaneous art creation often correlates with emotional themes later identified in therapy, suggesting that art accesses subconscious content (Chilton, 2017). For example, a child drawing a stormy sea might be expressing unarticulated fears, providing caregivers or therapists with a starting point for gentle exploration. However, parents must avoid over-interpreting artwork, as untrained analysis risks misreading symbols (Gussak & Rosal, 2016). A dark drawing might simply reflect a child’s love for “Batman’s colour” rather than distress. If recurring themes of fear or sadness emerge, consulting a licensed therapist is essential for accurate assessment (Cohen et al., 1988).

Decentring for Insight

Art therapy facilitates “decentring,” a process where children shift focus from a problem to the act of creating, gaining psychological distance that fosters insight. This aligns with cognitive diffusion techniques, which reduce emotional fixation by externalizing thoughts (Hayes et al., 2011). For example, a child upset about bullying might draw a scene of conflict, transforming an internal struggle into a tangible image they can examine or adjust. This externalization reduces emotional intensity, as shown in studies where visualizing feelings in art lowered distress (Slayton et al., 2010).

By observing their artwork, children gain new perspectives on their emotions or situations, enhancing problem-solving flexibility (Cohen-Yatziv & Regev, 2018). A small figure in a drawing might reveal feelings of vulnerability, sparking self-awareness that talk therapy might not uncover. This decentring process, rooted in psychological distance theory, helps children view challenges with clarity and resilience (Trope & Liberman, 2010).

Nurturing Relational Bonds

Art therapy’s relational dimension sets it apart from many therapeutic modalities. Collaborative art activities—such as painting a mural or creating a family sculpture—foster trust, empathy, and communication between children and caregivers. These shared experiences reinforce secure attachment, a cornerstone of healthy development (Bowlby, 1988). A study found that parent-child art therapy sessions improved perceived closeness and reduced conflict, as reported by participants (Proulx, 2003). Neuroscience further shows that positive social interactions during creative tasks enhance emotional regulation and relational trust (Schore, 2012).

Art also helps caregivers monitor their child’s emotional world, reducing the risk of unspoken struggles going unnoticed (Malchiodi, 2012). A child’s recurring use of aggressive imagery might prompt a caregiver to seek professional guidance, ensuring timely support. This visibility fosters proactive, attuned relationships, as caregivers gain insight into their child’s inner experiences (Drake et al., 2015).

Scientific Foundations

Art therapy’s efficacy is grounded in robust research. The Expressive Therapies Continuum (ETC) framework explains how art-making engages sensory, perceptual, and symbolic processes, allowing children to process emotions holistically (Hinz, 2019). Neuroscientific studies show that creative activities stimulate the prefrontal cortex, enhancing emotional regulation, while reducing amygdala activity, calming stress responses (Kaimal et al., 2017). A 2018 meta-analysis found that children in art therapy showed improved emotional intelligence and problem-solving compared to those in talk therapy (Gussak & Rosal, 2018). These findings underscore art therapy’s role as a scientifically validated tool for children’s well-being.

Addressing Misconceptions

- Myth: Art therapy is only for troubled children.

Fact: It benefits all children, promoting resilience and creativity. - Myth: Artistic talent is required.

Fact: The process, not the product, drives therapeutic value. - Myth: It’s just crafts.

Fact: Art therapy is a scientifically grounded therapeutic practice.

Conclusion

Art therapy is a vibrant, evidence-based approach to supporting children’s emotional, cognitive, and relational growth. By tapping into the unconscious, fostering insight through decentring, and nurturing caregiver-child bonds, it offers a joyful path to resilience. My guidebook equips families with 101 playful, accessible activities to bring these benefits home. Inspired by my years of practice as an art therapist, this resource invites you to witness your child’s inner world unfold through the universal language of art.

Some of the links on this blog are affiliate links, which means I may earn a commission if you make a purchase using the link. This comes at no additional cost to you. I only recommend products or services that I believe in and think will be valuable to my readers. I am also hoping you might consider purchasing my book 101 Art Therapy Exercises for Children: A Practical Guide for Parents and Mental Health Professionals. Thank you for supporting this blog!

Rostislava Buhleva-Simeonova is a psychologist, art therapist, and gamificator. She has worked with children, adults, and the elderly within various therapeutic programmes over the past eight years, all the while providing the much-needed playful twist that art and gamified experiences can bring to this sometimes uneasy setting. But it wasn’t until the birth of her daughter, Aurora, that this work took on an even deeper personal meaning. With her academic and real-life experience, honed through numerous trainings and sessions, she is currently authoring books and articles in the field of child psychology and development, offering expertise in art and play therapy to guide parents and caregivers, as well as professionals in the fields of social work and mental health, throughout various pivotal moments in children’s lives. Last but not least, all of her books have been “peer-reviewed” by her daughter, who testifies to the efficiency of these methods.

Rostislava Buhleva-Simeonova is a psychologist, art therapist, and gamificator. She has worked with children, adults, and the elderly within various therapeutic programmes over the past eight years, all the while providing the much-needed playful twist that art and gamified experiences can bring to this sometimes uneasy setting. But it wasn’t until the birth of her daughter, Aurora, that this work took on an even deeper personal meaning. With her academic and real-life experience, honed through numerous trainings and sessions, she is currently authoring books and articles in the field of child psychology and development, offering expertise in art and play therapy to guide parents and caregivers, as well as professionals in the fields of social work and mental health, throughout various pivotal moments in children’s lives. Last but not least, all of her books have been “peer-reviewed” by her daughter, who testifies to the efficiency of these methods.

References:

- Bowlby, J. (1988). A Secure Base: Parent-Child Attachment and Healthy Human Development. Basic Books.

- Chilton, G. (2017). Art therapy and the unconscious: A review. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 56, 45-52.

- Cohen, B. M., et al. (1988). The diagnostic drawing series: A systematic approach to art therapy evaluation. Arts in Psychotherapy, 15(1), 11-21.

- Cohen-Yatziv, L., & Regev, D. (2018). Art therapy and self-concept in children. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1342.

- Drake, J. E., et al. (2015). Art therapy in pediatric populations. Art Therapy: Journal of the American Art Therapy Association, 32(3), 112-119.

- Erikson, E. H. (1968). Identity: Youth and Crisis. Norton.

- Feinstein, D., & Krippner, S. (1988). Personal Mythology. Tarcher.

- Gussak, D. (2009). The effects of art therapy on male and female inmates. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 36(5), 286-293.

- Gussak, D., & Rosal, M. (2016). The Wiley Handbook of Art Therapy. Wiley-Blackwell.

- Hass-Cohen, N., & Carr, R. (2008). Art Therapy and Clinical Neuroscience. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Hayes, S. C., et al. (2011). Acceptance and commitment therapy. American Psychologist, 66(7), 581-592.

- Hinz, L. D. (2019). Expressive Therapies Continuum: A Framework for Using Art in Therapy. Routledge.

- Jung, C. G. (1964). Man and His Symbols. Doubleday.

- Kaimal, G., et al. (2017). Reduction of cortisol levels and participants’ responses following art making. Art Therapy: Journal of the American Art Therapy Association, 34(2), 74-80.

- Linesch, D. (2016). Art Therapy and the Family. Routledge.

- Lusebrink, V. B. (2004). Art therapy and the brain. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 31(3), 125-135.

- Malchiodi, C. A. (2012). Handbook of Art Therapy. Guilford Press.

- Panksepp, J. (1998). Affective Neuroscience. Oxford University Press.

- Piaget, J. (1970). The Child’s Conception of the World. Routledge.

- Proulx, L. (2003). Strengthening Emotional Ties through Parent-Child-Dyad Art Therapy. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Reynolds, M. W., et al. (2000). The efficacy of art therapy: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 20(6), 697-709.

- Schore, A. N. (2012). The Science of the Art of Psychotherapy. Norton.

- Shonkoff, J. P., & Phillips, D. A. (2000). From Neurons to Neighborhoods. National Academies Press.

- Slayton, S. C., et al. (2010). Outcome studies on the efficacy of art therapy. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 37(4), 247-255.

- Trope, Y., & Liberman, N. (2010). Construal-level theory of psychological distance. Psychological Review, 117(2), 440-463.

- Van der Kolk, B. (2014). The Body Keeps the Score. Penguin.