The Psychological Benefits of Role-Play for Children

I’ve spent the last eight years helping parents and caregivers understand how children grow emotionally, socially, and cognitively. And if there’s one thing I keep coming back to, it’s this: role-play isn’t just cute. It’s essential. When a child turns the couch into a pirate ship, they’re not “passing time.” They’re running a self-directed masterclass in emotional regulation, problem-solving, and empathy. Let me walk you through what we now know, broken down by age, with clear ties to the big theories (Freud, Piaget, Vygotsky, Erikson).

Role play is a fundamental aspect of child development, serving as a vital tool for learning and socialization. This form of imaginative play allows children to explore different identities, contexts, and relationships, enabling them to better understand their surroundings and themselves. Historically, prominent figures in classical psychology have emphasized the importance of play in a child’s growth. Psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud, for example, proposed that play is a means through which children can express unresolved conflicts and desires, providing them with a safe environment to explore complex emotions.

Building on Freud’s theories, Lev Vygotsky, a leading developmental psychologist, introduced the concept of the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD), highlighting that children learn best when they engage in activities slightly above their current capabilities, often achieved through guided role play. Vygotsky posited that by adopting various roles, children can practice new skills, think critically, and solve problems collaboratively, which ultimately contributes to cognitive and social development.

Contemporary research continues to support the significance of role play in child development. Meta-analyses have shown that imaginative play fosters essential life skills, including empathy, emotional regulation, and creativity. For instance, when children enact scenarios that mimic real-life situations, they not only learn about social norms and dynamics but also develop an understanding of different perspectives. This ability to engage in role reversal is crucial for cultivating empathy, allowing children to relate to the feelings and experiences of others.

Role play serves as a significant tool in the cognitive development of children, offering them unique opportunities to explore and understand their environment. The foundational theories of cognitive growth established by classical psychologists, particularly Jean Piaget, highlight the importance of play in intellectual engagement. Piaget asserted that children learn through experiences as they manipulate and interact with objects and scenarios. His stages of cognitive development indicate that role play nurtures essential skills at various ages, particularly during the preoperational stage (ages 2-7), where imaginative play flourishes.

Different age ranges experience varying benefits from role play. Younger children, typically aged 2 to 4, may focus on imitation and basic role taking, while older children, around ages 5 to 7, take a more complex approach involving elaborate narratives and role dynamics. This progression signifies the critical role of imaginative play in forming a foundation for cognitive tasks that they will encounter later in academic settings. Enhanced problem-solving skills, critical thinking, and language proficiency arise through these valuable interactions, underscoring the necessity of role play in child development.

Theory in Action

Role-play is where Piaget’s symbolic thinking, Vygotsky’s social scaffolding, and Erikson’s emotional milestones meet in everyday moments. A child turns a stick into a magic wand (Piaget’s symbolic thinking), debates its powers with a playmate (Vygotsky’s social scaffolding), and casts a daring spell to save the kingdom without fear of real-world judgment (Erikson’s emotional milestone).

Contemporary research confirms this integration drives measurable gains in cognitive flexibility, self-regulation, and emotional confidence. Children who engage in regular pretend play show stronger problem-solving, better impulse control, and deeper social bonds—outcomes that predict success in social settings and relationships.

Toddlers (2–3 Years): The Birth of “As If”

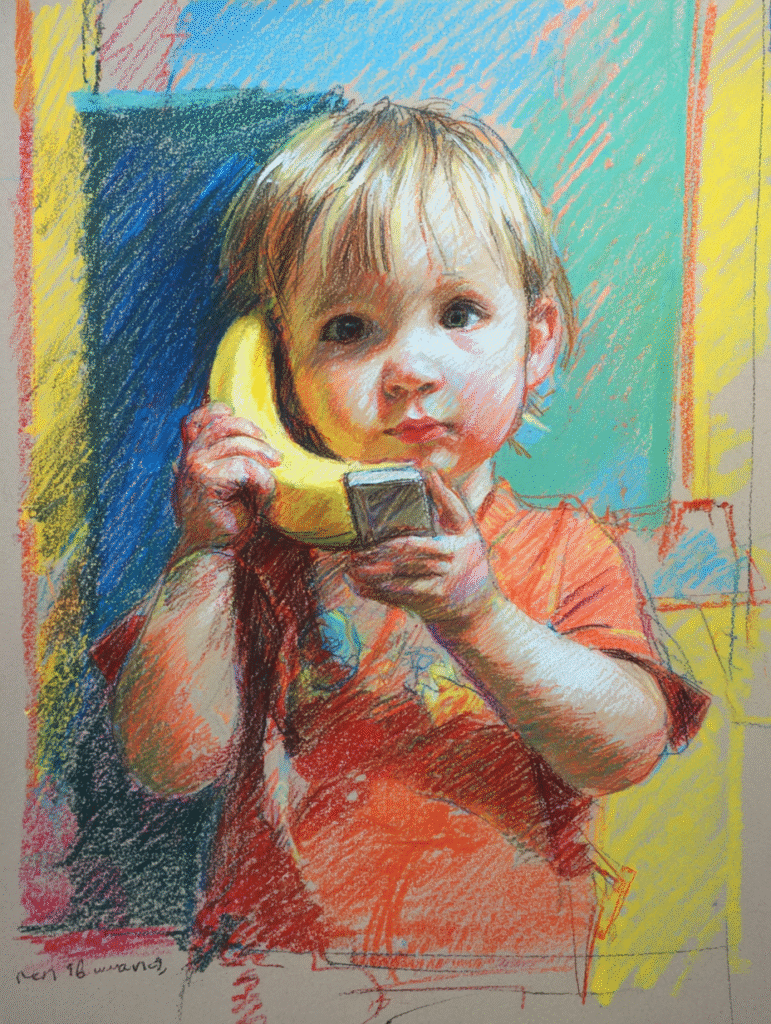

This is Piaget’s symbolic play at its essence. A toddler holding a banana, leaf, or anything at all to their ear and saying “Hello?” isn’t confused—they’re discovering that any object can stand for a phone, laying the groundwork for abstract thinking in reading, math, and beyond.

When you join softly—“Who’s calling? Is it Grandma?”—you’re fostering Bowlby’s secure attachment through co-regulation.

Research backs this: toddlers with daily caregiver-guided pretend play show earlier empathy and fewer tantrums by age 3 (Hoff et al., 2025). They’re not just calmer—they’re more expressive and connected.

Toddler Role-Play Exercise: “Magic Phone”

Goal: Spark symbolic thinking (Piaget) and emotional co-regulation (Bowlby)

Gather props: Offer 3–4 safe, everyday items (banana, wooden spoon, scarf, etc.)Start simple: Hold one item to your ear and say in a warm, playful voice, “Ring ring! Hello?”

Invite imitation: Hand your child an item and ask, “Who’s calling you?”

Follow their lead: If they say “Dada,” respond, “Hi Dada! We miss you!”

Name the feeling: Once or twice, gently label: “You look excited to talk to Dada!”

End softly: After 5–10 minutes, say, “Phone needs a nap—night-night!” and tuck the item away together.

Preschoolers (4–6 Years): The Social Stage Comes Alive

Now play turns collaborative. Children assign roles, rewrite rules, and navigate disagreements—all within the safety of “let’s pretend.” This is Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development in motion: a slightly older peer or adult helps the child stretch just beyond what they can do alone.

A child declaring “The astronaut needs a hug!” isn’t being silly—they’re practicing theory of mind, the ability to imagine another’s inner world. When you ask, “Why do you think the astronaut feels that way?” you’re weaving emotion into words, guiding them from raw impulse to genuine empathy.

This is also Erikson’s initiative versus guilt stage. In real life, bold ideas risk criticism. In play, they’re celebrated. Every successful “mission” reinforces: “I can lead. I can create. I can recover from mistakes.”

Studies show preschoolers in frequent sociodramatic play form stronger friendships and resolve conflicts 40% more effectively (Bergen, 2024). Their language grows richer too—retelling stories with 30% more detail (Nicolopoulou et al., 2025).

Preschool Role-Play Exercise: “Space Rescue Mission”

Goal: Build theory of mind (Vygotsky), emotional vocabulary, and initiative (Erikson)

Set the scene: Gather 4–5 props (sofa cushions for a“spaceship,” scarves for capes, toy animals as “crew”). Say, “The spaceship is stuck on the moon—how can you help!”

Assign roles freely: Let children choose: pilot, engineer, doctor, or alien. No corrections—honor their pick. If two aliens emerge – let them be.

Launch the story: Start with a problem: “The engine won’t start. What is everyone doing?”

Celebrate every move: Cheer small wins: “Wow, turning the cushion into a lifeboat is genius!” If conflict arises (“I’m the pilot!”), reflect: “What if we need two pilots to fly this big rocket? How could you share the controls?”

Wrap with reflection: After 15–20 minutes, gather: “What felt the most exciting? Which part made you feel proud? Did you enjoy your role?

Children practice perspective-taking (theory of mind), negotiate rules (Vygotsky’s ZPD), and lead without fear (Erikson’s initiative).

School-Age Kids (7–12 Years): Mastery Through Story

Pretend play doesn’t end—it evolves. Tabletop games, school dramas, or backyard epics become arenas for Erikson’s industry versus inferiority. Success in a campaign isn’t about grades; it’s about contribution, strategy, and belonging.

A child running a Dungeons & Dragons session practices executive function—planning, adapting, delaying gratification—while exploring ethical reasoning in a low-stakes world. When a character fails, the player reflects, adjusts, and tries again. That’s resilience in action.

Vygotsky’s influence lingers: older peers or a parent as “game master” provide just enough structure to challenge without overwhelming. The result? Children who feel competent, connected, and capable.

Long-term studies show kids with rich early pretend play enter middle school with stronger self-regulation and higher academic confidence (Golinkoff & Hirsh-Pasek, 2024). Structured fantasy play even reduces ADHD symptoms by 50% in therapeutic settings (Hennessy et al., 2025).

School-Age Role-Play Exercise: “Magical Quest”

Goal: Foster executive function, ethical reasoning (Erikson’s industry), and resilience through guided structure (Vygotsky)

Prepare the quest: Draw a simple map on paper (forest, cave, village) and list 3–4 “challenges” (find the lost key, convince the grumpy troll, share the treasure). Decide together what the treasure should be.

Choose roles: Let kids pick their role (anything they want to be) and if they struggle assign one—healer, knight, fairy and other mythological magical creatures. Encourage one to be “quest leader” (rotates weekly).

Set clear rules: 10-sided die for luck, each player gets one “retry token” if a plan fails. Results below five mean the plan has failed.

Play in rounds:

Plan: “How do we cross the river?”

Act: The children use backyard props or imaginary tools and storytelling to cross the river.

Outcome: The die determines the success of the plan. Remember to always provide an explanation as to why the plan has failed.

Handle setbacks: If someone “loses,” say: “Your character fell—but what can they learn for the next try?”

End with pride: After 45–60 minutes, circle up: “Who felt like a real hero today? What was the best part of the adventure? Did you enjoy your role? What was your greatest feature?”

Kids practice planning and adaptation (executive function), weigh moral choices (ethical reasoning), and bounce back from failure (resilience). Rotate the quest leader to build leadership

Theory Meets Therapy

Clinicians now use therapeutic role-play to help children process anxiety, trauma, or social struggles. A child who can’t say “I’m scared of the dark” might whisper it through a puppet. A teen wrestling with identity might explore it safely as a fantasy hero.

This builds on Freud’s idea of play as the child’s language, now validated in programs like TOTEM, where dramatic play after disasters cuts anxiety by 35% and sleep issues by 28% (Capurso et al., 2025). The mechanism? Externalization + rehearsal. Big feelings become manageable when acted out, reflected on, and resolved in character.

Bring Theory Home

For toddlers, offer 20–30 minutes daily with simple props. Narrate and mirror, but don’t direct. For preschoolers, aim for 45–60 minutes of group play. Provide a spark—“The spaceship is stuck!”—then coach emotions. For school-age kids, schedule a weekly 60-minute story session. Supply structure (rules, roles), then cheer their leadership.

Challenges and Considerations in Implementing Role Play

While role play can significantly enhance child development, its successful implementation requires careful consideration of various challenges. One crucial aspect is supervision, as children often require guidance to ensure that their play remains productive and safe. Educators and parents should actively engage with children during role play, providing scaffolding support that aids in the learning process without overshadowing their creativity. This leads to a better understanding of the dynamics of play and equips children with valuable social skills while fostering an atmosphere of trust and support.

Inclusivity represents another important consideration. It is vital that role play activities accommodate children of different abilities, cultural backgrounds, and personalities. Educators and parents must strive to find scenarios that allow all participants to engage fully, promoting empathy and understanding among peers. This can be achieved by incorporating a diverse range of characters, settings, and narratives that reflect the children’s experiences and environments, ensuring that every child feels seen and valued in the role play situation.

Moreover, finding the right balance between guided and free play is essential for fostering a positive learning environment. While structured role play can provide clear objectives and learning outcomes, too much guidance may stifle children’s imagination. Conversely, unstructured play can lead to confusion and frustration if children lack direction. It is beneficial to establish a flexible framework that encourages exploration while still offering a safety net. This balance can be achieved through promoting open-ended activities that allow children to navigate their own narratives while receiving gentle direction when necessary.

To create safe and supportive environments for effective role play, educators and parents should encourage an atmosphere of respect and cooperation. Establishing clear expectations, promoting conflict resolution skills, and providing adequate time for reflection can greatly enhance the role play experience, making it a valuable tool for child development.

The Bottom Line

Role-play isn’t a luxury—it’s developmental infrastructure. It’s where Piaget’s symbols turn into tools, Vygotsky’s scaffolding forges connection, and Erikson’s crises resolve into confidence.

So next time your child drapes a towel over their shoulders and announces, “I’m the superhero—help me stop the volcano!”—say yes. You’re not just playing. You’re building a mind and heart that will thrive for a lifetime.

Some of the links on this blog are affiliate links, which means I may earn a commission if you make a purchase using the link. This comes at no additional cost to you. I only recommend products or services that I believe in and think will be valuable to my readers. I am also hoping you might consider purchasing my book 101 Art Therapy Exercises for Children: A Practical Guide for Parents and Mental Health Professionals. Thank you for supporting this blog!

Rostislava Buhleva-Simeonova is a psychologist, art therapist, and gamificator. She has worked with children, adults, and the elderly within various therapeutic programmes over the past eight years, all the while providing the much-needed playful twist that art and gamified experiences can bring to this sometimes uneasy setting. But it wasn’t until the birth of her daughter, Aurora, that this work took on an even deeper personal meaning. With her academic and real-life experience, honed through numerous trainings and sessions, she is currently authoring books and articles in the field of child psychology and development, offering expertise in art and play therapy to guide parents and caregivers, as well as professionals in the fields of social work and mental health, throughout various pivotal moments in children’s lives. Last but not least, all of her books have been “peer-reviewed” by her daughter, who testifies to the efficiency of these methods.

References (Foundational & Contemporary)

Piaget, J. (1962). Play, Dreams and Imitation in Childhood.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in Society.

Bodrova, E., & Leong, D. J. (2023). Tools of the Mind (3rd ed.).

Erikson, E. H. (1950). Childhood and Society.

Yogman, M., et al. (2025). The Power of Play. Pediatrics.

Child Mind Institute. (2025). Pretend Play and Emotional Skills.

Hoff, E., et al. (2025). Parental Perceptions of Pretend Play. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology.

Capurso, M., et al. (2025). The TOTEM Program. Child Psychiatry & Human Development.

Bergen, D. (2024). Pretend Play and Social Competence. Early Education and Development.

Nicolopoulou, A., et al. (2025). Storytelling Through Play. Journal of Child Language.

Hennessy, E., et al. (2025). D&D as ADHD Therapy. Journal of Attention Disorders.

Golinkoff, R. M., & Hirsh-Pasek, K. (2024). Play it Forward. American Educator.